“Breathless”: An artistic tribute to Godard and the French new wave

“What is your greatest ambition in life?” “To become immortal… and then die.” – Jean-Luc Godard

In September, acclaimed French film director, Jean-Luc Godard, passed away. Often regarded as one of the foremost directors of the French New Wave, he aimed to challenge accepted cinematic conventions and revolutionized modern film-making in the process.

The New Wave was a clear deviation from pre-existing cinematic expectations of the time. It featured existentialist undertones, morally gray characters and experimental camera work. Godard’s 1960 debut film, “Breathless (Á Bout de Souffle),” is considered one of the first and most defining films of the movement.

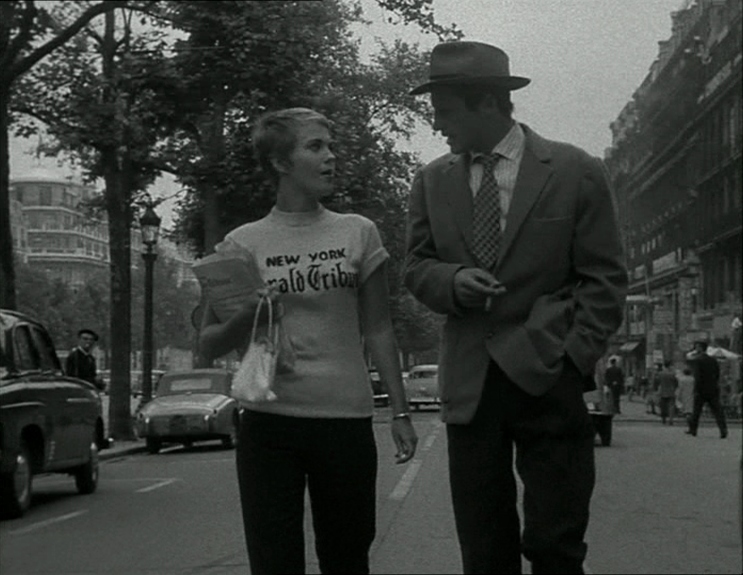

“Breathless” follows the relationship between easygoing car thief Michel (Jean-Paul Belmondo) and American journalist Patricia (Jean Seberg). After stealing a car and killing a police officer, Michel must evade the authorities, collect money from debtors and flee to Rome. However, his biggest goal, and biggest challenge, is making Patricia fall in love with him. The two attempt to lay low Bonnie and Clyde-style, but an unexpected twist ultimately defines their relationship.

Belmondo’s performance is relaxed yet self-assured, and is best seen in Michel’s ability to spew biting yet humorous criticisms of everyone he meets. One of the most impressive parts of his performance is that he is either smoking or holding a cigarette in almost every scene. All the smoke visible on-screen is enough to make the viewer feel breathless.

Seberg embodies the “French girl” aesthetic, even with a purposely prominent American accent. Her innocent appearance contrasts her unexpectedly villainous role, especially in the final scene where her naïveté becomes especially duplicitous.

The interactions between the two leads feel authentic and unstructured, mostly because the film was unscripted and largely improvised. This openness is the most admirable characteristic of the film and it allows the viewer to feel as though they are listening to real conversations. It is refreshing to see a film set during this time period that was not confined by the standards of the American Hays Code. This code declared that films should not depict crime or wrongdoing in a positive light, in an attempt to avoid lowering the moral standards of those who watched them.

The camera moves to meet or catch up with actors as they meander down the streets of Paris. The camera shakes as it pans, as if it is intentionally held by an unsteady hand. Jump cuts, an editing technique that shows sudden forward progressions in time, are used frequently throughout the film to move the action along. Instead of opting for smooth transitions, the abruptness of the cuts creates a fast and somewhat unorthodox pace.

This movie is perfect for Francophiles, stylistic cinema enthusiasts and fans of unconventional romances. Godard’s ability to interplay freshness and realism in the midst of the on-screen chaos makes “Breathless” worth a watch even 60 years after its release.

Hannah is a senior at Naperville North and is excited to begin her first year with the North Star. She hopes to exercise her writing abilities, learn new...