Let’s talk about it: OCD

Light switch on. Light switch off. Light switch on. Light switch off.

On-off-on-off-on-off-on.

Eleven times is the perfect number. It is an amount that appeases. It reassures. It is a compulsive obsession. This is one manifestation of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. However, contrary to popular belief, the disorder is not always as apparent.

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is characterized by uncontrollable, recurring thoughts and habits. According to SchoolBehavior.com, obsessions are frequent thoughts, urges, or images that foster intrusive thoughts, leading to agitation and anxiety. Compulsions are the behaviors that result from the obsessions, mental acts that are performed in order to pacify distress or thwart off a dreaded situation.

The behaviors that constitute OCD— more specifically, the forms of OCD that are visible— have been inducted into our culture as a run-of-the-mill quirk. The words “I am so OCD right now” have seeped into our society’s vocabulary as a punchline.

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder has been productized into a fad in popular culture, as recurring references of the physical, compulsory aspects of OCD emerge in mass media, manifesting in characters such as Monica in Friends or Sheldon in The Big Bang Theory.

According to licensed clinical psychologist Melanie Santos, tangible compulsions are easier to understand than repetitive, obsessive thoughts, such as unreasonable and intrusive fears or commiting acts of violence on a close family member or friend. Naturally, society gravitates towards this narrow, easy to swallow concept of OCD.

“A lot of people associate [OCD] with cleanliness, which is a very small population. OCD can be any symptom that falls into [obsessions or compulsions]. People could be really obsessive about getting sick or being clean, but they can also have really scary thoughts about potentially hurting someone… [or] causing a fire or a flood,” Santos explained. “In terms of just the media providing information, it’s a lot easier to show someone washing their hands excessively than showing someone having bad thoughts— that doesn’t make for good TV.”

Yet the obsessive thoughts that partially comprise the disorder hardly ever reach the limelight. The compulsions, the only material aspect of the disorder, are the obsessions. Common misconceptions on how these thoughts transpire result in stigma against the non-physical component of the disorder.

Consequently, stigmas about OCD leave those with the disorder, particularly adolescents, struggling to connect with their peers. The affected party is often floating in the purgatory of the common societal perception of OCD, as it indecisively toggles between taboo and mainstream punchlines.

“With teens I think it’s even more crucial to intervene as soon as possible in the correct way,” Jane Bodine, a licensed clinical professional counselor, explained. “It’s so essential for teens to feel like they connect with other teens and almost every teen that has come to me was severe or extreme OCD and started to isolate [themselves].”

Those affected by OCD may not even recognize their symptoms at first. NNHS junior Jack Cook recalls being oblivious to the disorder at first, but soon felt ostracized by his symptoms.

“My parents would tell me ‘you [have to] stop spitting, that’s not normal’ and that made me feel weird because I’m different from everyone else,” Cook said. “That was weird for me to understand and be okay with.”

Cook expressed his confliction between knowing his habits are irrational and feeling unexplainably afraid of not doing them. According to Cook, these intrusive thoughts are controlling and have a significant effect on his daily life. Gino Campise, an NNHS Communication Arts teacher, shares similar feelings.

“There’s no reason to expect [perfection] because that puts more anxiety which kind of stifles one’s ability then to take risks,” Campise said. “There were times when I wouldn’t take risks because I wasn’t sure… what if it goes wrong?”

Campise, who is open with his students about his OCD, hopes that by sharing this more personal side of his life, his students will walk away with new perspectives and recognize there are ways to manage OCD.

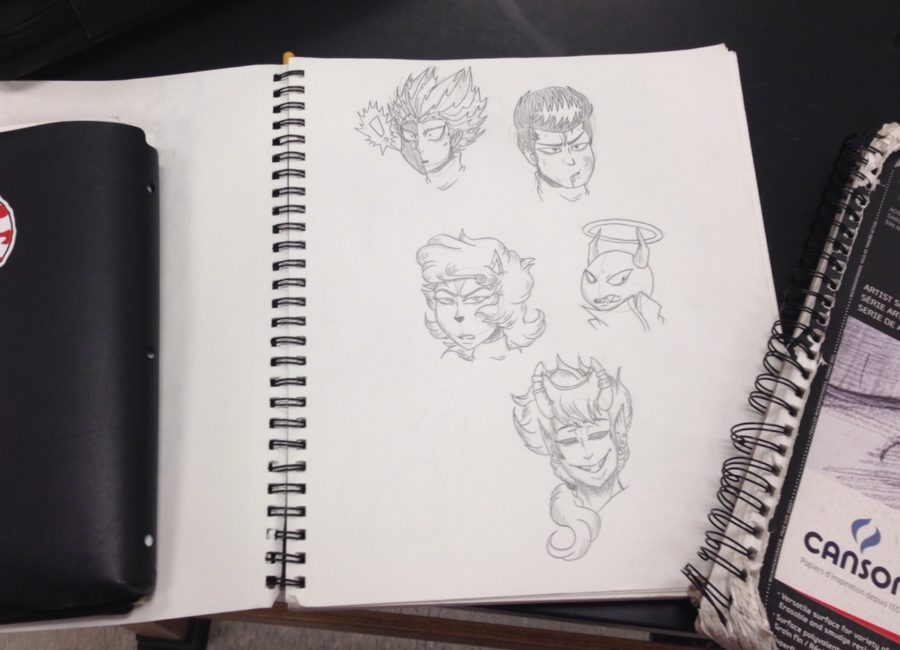

Cook has taken to art as a distraction to break away from overwhelming anxiety.

“I’ll draw and that easily takes my mind off things… and I end up forgetting what the bad thought was. Everyone has their own ways of coping with it,” Cook said.

Cook credits talking through problems with a therapist in developing a better understanding of his own thoughts and how to overcome them. For Cook, examining the process behind the symptoms has been immeasurably useful. He feels that anyone struggling with OCD should take advantage of opportunities, with a therapist or not, to explore their symptoms.

“It is a very personal thing because everyone responds to their thoughts differently and deals with them differently,” Cook said. “It’s helpful to figure out what works for you.”

Robyn is a senior at Naperville North returning for her second year on The North Star and her first year as the Multimedia Producer. She is looking forward...