Hitting your stride: part two

Preparing for an audition on the best note possible.

Part one focused on what to consider when choosing your college audition repertoire. This time, let’s take a look at how to prepare your selected pieces.

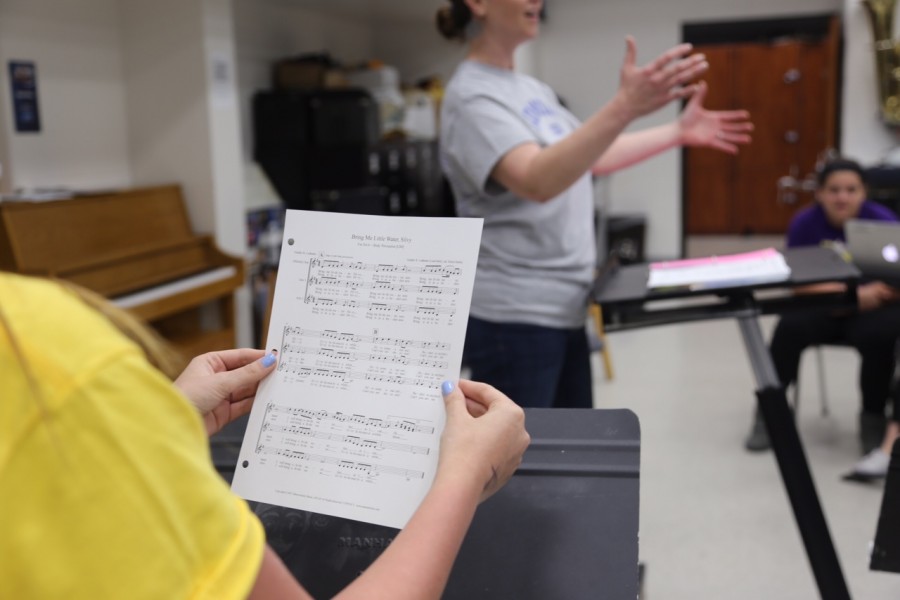

When a musician first gets a new piece of music, figuring out how to dissect it can be perplexing. Should they start with the words or the notes? How do they go about making a connection with the music?

There are many different philosophies on where exactly one should begin when learning a new piece. According to voice teacher Dr. Jennifer Barnickel-Fitch, DMA and a voice teacher at College of DuPage, the first place to start is with learning your translations and pronunciations.

A student should write the translations into their music. Personally, I put the literal translations above the words, and the poetic translation underneath the words. One can also write in pronunciation reminders on a “working copy” of the music. Keeping a clean, master copy on hand to give to the accompanist something readable is also important.

Fitch then recommends learning the rhythm and melody separately. After that, she says, you can start to put together the rhythm and the words, then the melody and the rhythm.

This is best demonstrated through analyzing one of my own audition pieces, When I Have Sung My Songs by Ernest Charles. One of the most important phrases in this piece was “that I could never, never sing again.”

Right off the bat, we know that “never” is important because it is repeated (when you have a repeated word, it’s often effective to do something different the second time it is sung).

As far as determining what to change, ask yourself, “why is my character saying this word twice?” To me, this song is about a woman whose partner is questioning her faithfulness and commitment to him.

There is a buildup to the first “never,” and when you finally reach it, it’s a big moment–the climax of the piece. Her emotions are overwhelming, and she is trying hard to reach her partner. When she finally gets out that first “never,” the phrase backs off. The rest of the phrase she sings to herself, so it is quieter and more resigned. She is telling herself what she knows is true in her heart–she knows it’s over between them.

It’s easy to pick these things up when you really pay attention to every detail in the music.

Meg Stoltz, marketing associate at the Lyric Opera of Chicago and vocal technique teacher at Merit School of Music, said she recommends looking at other singers performing the same piece.

“Their body language is going to tell you so much that you might not know from looking at a piece,” Stoltz said.

Still, she said she cautions singers to make sure their interpretation of the piece is true to themselves.

“You can still, you know, listen around, look around, just to kind of get more ideas, but once you’re in a position to own it, really it’s time to own it,” Stoltz said.